Hugh Hefner, who created Playboy magazine and spun it into a media and entertainment-industry giant — all the while, as its very public avatar, squiring attractive young women (and sometimes marrying them) well into his 80s — died on Wednesday at his home, the Playboy Mansion near Beverly Hills, Calif. He was 91.

His death was announced by Playboy Enterprises.

Hefner the man and Playboy the brand were inseparable. Both advertised themselves as emblems of the sexual revolution, an escape from American priggishness and wider social intolerance. Both were derided over the years — as vulgar, as adolescent, as exploitative, and finally as anachronistic. But Mr. Hefner was a stunning success from his emergence in the early 1950s. His timing was perfect.

He was compared to Jay Gatsby, Citizen Kane and Walt Disney, but Mr. Hefner was his own production. He repeatedly likened his life to a romantic movie; it starred an ageless sophisticate in silk pajamas and smoking jacket, hosting a never-ending party for famous and fascinating people.

The first issue of Playboy was published in 1953, when Mr. Hefner was 27 years old, a new father married to, by his account, the first woman he had slept with.

He had only recently moved out of his parents’ house and left his job at Children’s Activities magazine. But in an editorial in Playboy’s inaugural issue, the young publisher purveyed another life:

“We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”

This scene projected an era’s “premium boys’ style,” Todd Gitlin, a sociologist at Columbia University and the author of “The Sixties,” said in an interview. “It’s part of an ensemble with the James Bond movies, John F. Kennedy, swinging, the guy who is young, vigorous, indifferent to the bonds of social responsibility.”

Mr. Hefner was reviled, first by guardians of the 1950s social order — J. Edgar Hoover among them — and later by feminists. But Playboy’s circulation reached one million by 1960 and peaked at about seven million in the 1970s.

Long after other publishers made the nude “Playmate” centerfold look more sugary than daring, Playboy remained the most successful men’s magazine in the world. Mr. Hefner’s company branched into movie, cable and digital production, sold its own line of clothing and jewelry, and opened clubs, resorts and casinos.

The brand faded over the years, and by 2015 the magazine’s circulation had dropped to about 800,000 — although among men’s magazines it was outsold by only one, Maxim, which was founded in 1995.

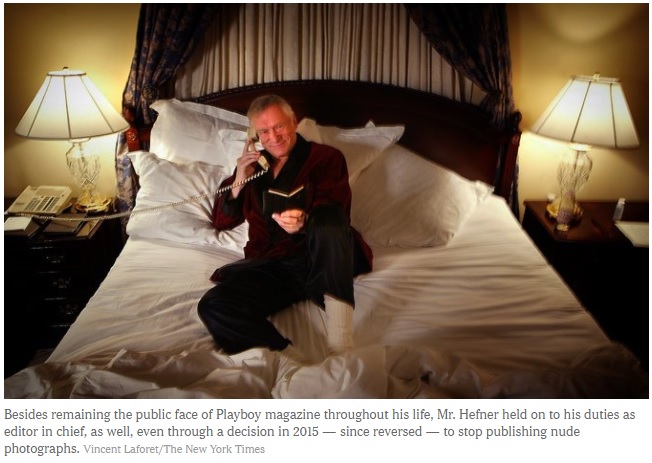

Mr. Hefner remained editor in chief even after agreeing to the magazine’s startling decision in 2015 to stop publishing nude photographs. Mr. Hefner handed over creative control of Playboy last year to his son Cooper Hefner. Playboy Enterprises’ chief executive, Scott Flanders, acknowledged that the internet had overrun the magazine’s province: “You’re now one click away from every sex act imaginable for free. And so it’s just passé at this juncture.” The magazine’s website, Playboy.com, had already been revamped as a “safe for work” site. Playboy was no longer illicit. (Early this year, the magazine brought back nudes.)

Mr. Hefner began excoriating American puritanism at a time when doctors refused contraceptives to single women and the Hollywood production code dictated separate beds for married couples. As the cartoonist Jules Feiffer, an early Playboy contributor, saw the 1950s, “People wore tight little gray flannel suits and went to their tight little jobs.”

“You couldn’t talk politically,” Mr. Feiffer said in the 1992 documentary “Hugh Hefner: Once Upon a Time.” “You couldn’t use obscenities. What Playboy represented was the beginning of a break from all that.”

Playboy was born more in fun than in anger. Mr. Hefner’s first publisher’s message, written at his kitchen table in Chicago, announced, “We don’t expect to solve any world problems or prove any great moral truths.”

Still, Mr. Hefner wielded fierce resentment against his era’s sexual strictures, which he said had choked off his own youth. A virgin until he was 22, he married his longtime girlfriend. Her confession to an earlier affair, Mr. Hefner told an interviewer almost 50 years later, was “the single most devastating experience of my life.”

In “The Playboy Philosophy,” a mix of libertarian and libertine arguments that Mr. Hefner wrote in 25 installments starting in 1962, his message was simple: Society was to blame. His causes — abortion rights, decriminalization of marijuana and, most important, the repeal of 19th-century sex laws — were daring at the time. Ten years later, they would be unexceptional.

“Hefner won,” Mr. Gitlin said in a 2015 interview. “The prevailing values in the country now, for all the conservative backlash, are essentially libertarian, and that basically was what the Playboy Philosophy was.

“It’s laissez-faire. It’s anti-censorship. It’s consumerist: Let the buyer rule. It’s hedonistic. In the longer run, Hugh Hefner’s significance is as a salesman of the libertarian ideal.”

The Playboy Philosophy advocated freedom of speech in all its aspects, for which Mr. Hefner won civil liberties awards. He supported progressive social causes and lost some sponsors by inviting black guests to his televised parties at a time when much of the nation still had Jim Crow laws.

The magazine was a forum for serious interviews, the subjects including Jimmy Carter (who famously confessed, “I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times”), Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre and Malcolm X. In the early days Mr. Hefner published Ray Bradbury (Playboy bought his “Fahrenheit 451” for $400), Herbert Gold and Budd Schulberg. It later drew, among many others, Vladimir Nabokov, Kurt Vonnegut, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, James Baldwin, John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates.

Hugh Marston Hefner was born on April 9, 1926, the son of Glenn and Grace Hefner, Nebraska-born Methodists who had moved to Chicago. Decades later, he still told interviewers that he grew up “with a lot of repression,” and he often noted that his father was a descendant of William Bradford, the Puritan governor of the Plymouth Colony.

Though father and son reached an accommodation — the elder Mr. Hefner became Playboy’s accountant and treasurer — neither changed moral compass points. Glenn Hefner, who died in 1976, said he had never looked at the pictures in the magazine.

As a child, Mr. Hefner spent hours writing horror stories and drawing cartoons. At Steinmetz High School, he said, “I reinvented myself” as the suave, breezy “Hef,” newspaper cartoonist and party-loving leader of what he called “our gang.” At the University of Illinois, after serving in the Army, he edited the humor magazine and started a photo feature called “Co-ed of the Month.”

He married a high school classmate, Millie Williams, and began what he described as a deadening slog into 1950s adulthood: He took a job in the personnel department of a cardboard-box manufacturer. (He said he quit when asked to discriminate against black applicants.) He wrote advertising copy for a department store, and then for Esquire magazine. He became circulation promotion manager of another magazine, Children’s Activities.

Meanwhile he was plotting his own magazine, which was to be, among other things, a vehicle for his slightly randy cartoons. The first issue of Playboy was financed with $600 of his own money and several thousand more in borrowed funds, including $1,000 from his mother. But his biggest asset was a nude calendar photograph of Marilyn Monroe. He had bought the rights for $500.

Plenty of other men’s magazines showed nude women, but most were unabashedly crude and forever dodging postal censors. Mr. Hefner aimed to be the first to claim a mainstream readership and mainstream distribution.

When Playboy reached newsstands in December 1953, its press run of 51,000 sold out. The publisher, instantly famous, would soon become a millionaire; after five years, the magazine’s annual profit was $4 million and its rabbit logo was recognized around the world.

Mr. Hefner ran the magazine and then the business empire largely from his bedroom, working on a round bed that revolved and vibrated. At first he was reclusive and frenetic, powered past dawn by amphetamines and Pepsi-Cola. In later years, even after giving up Dexedrine, he was still frenetic, and still fiercely attentive to his magazine.

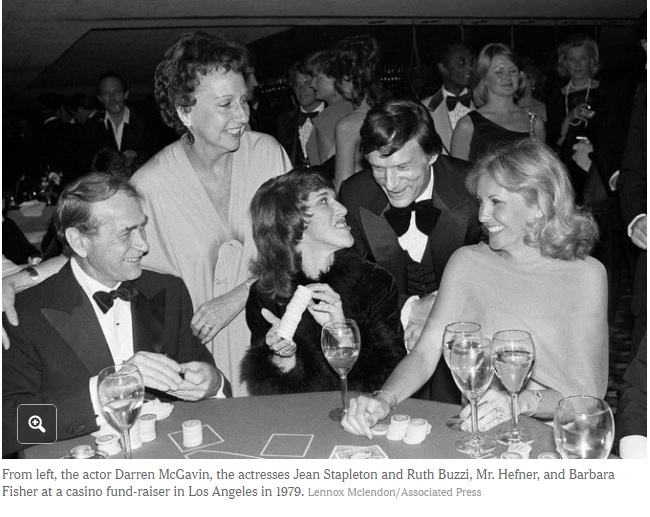

His own public playboy persona emerged after he left his wife and children, Christie and David, in 1959. That year his new syndicated television series, “Playboy’s Penthouse,” put the wiry, intense Mr. Hefner, pipe in hand, in the nation’s living rooms. The set recreated his mansion on North State Parkway, rich in sybaritic amusements, where he greeted entertainers like Tony Bennett, Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole, and intellectuals and writers like Max Lerner, Norman Mailer and Alex Haley, while bunches of glamorous young women milled around. (A later TV show, “Playboy After Dark,” was syndicated in 1969 and 1970.)

In the Playboy offices, life imitated image. Mr. Hefner told a film interviewer that in the early days, yes, “everybody was coupling with everybody,” including him. He later estimated that he slept with more than 1,000 women. Over and over, he would say, “I’m the boy who dreamed the dream.”

Friends described him as both charming and shy, even unassuming, and intensely loyal. “Hef was always big for the girls who got depressed or got in a jam of some sort,” the artist LeRoy Neiman, one of the magazine’s main illustrators for more than 50 years, said in an interview in 1999. “He’s a friend. He’s a good person. I couldn’t cite anything he ever did that was malicious to anybody.”

At the same time, Mr. Hefner adored celebrity, his and others’. Mr. Neiman, who sometimes lived at the Playboy Mansion, said: “It was nothing to breakfast there with comedians like Mort Sahl, professors, any kind of person who had something on his mind that was controversial or new. At the parties in the early days, Alex Haley used to hang around. Tony Curtis and Hugh O’Brian were always there. Mick Jagger stayed there.”

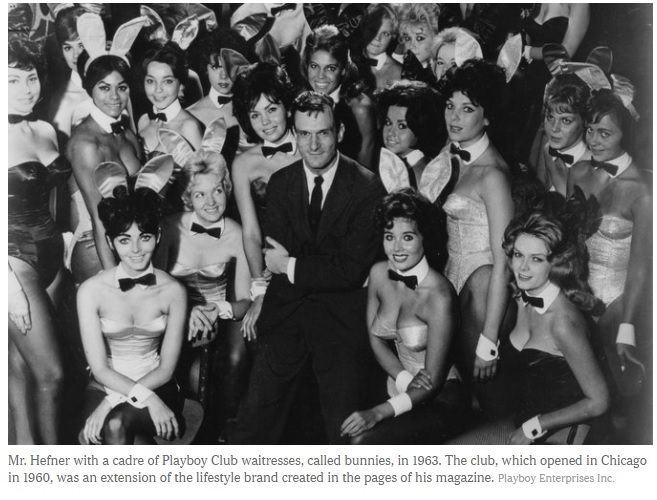

The glamour rubbed off on Mr. Hefner’s new enterprise, the Playboy Club, which was crushingly popular when it opened in Chicago in 1960. Dozens more followed. The waitresses, called bunnies, were trussed in brief satin suits with cotton fluffs fastened to their derrières.

One bunny briefly employed in the New York club would earn Mr. Hefner’s lasting enmity. She was an impostor, a 28-year-old named Gloria Steinem who was working undercover for Show magazine. Her article, published in 1963, described exhausting hours, painfully tight uniforms (in which half-exposed breasts floated on wadded-up dry cleaner bags) and vulgar customers.

Another feminist critic, Susan Brownmiller, debating Mr. Hefner on a television talk show, asserted, “The role that you have selected for women is degrading to women because you choose to see women as sex objects, not as full human beings.” She continued: “The day you’re willing to come out here with a cottontail attached to your rear end. …”

Mr. Hefner responded in 1970 by ordering an article on the activists then called “women’s libbers.” In an internal memo, he wrote: “These chicks are our natural enemy. What I want is a devastating piece that takes the militant feminists apart. They are unalterably opposed to the romantic boy-girl society that Playboy promotes.”

The commissioned article, by Morton Hunt, ran with the headline “Up Against the Wall, Male Chauvinist Pig.” (The same issue contained an interview with William F. Buckley Jr., fiction by Isaac Bashevis Singer and an article by a prominent critic of the Vietnam War, Senator Vance Hartke of Indiana.)

Mr. Hefner said later that he was perplexed by feminists’ apparent rejection of the message he had set forth in the Playboy Philosophy. “We are in the process of acquiring a new moral maturity and honesty,” he wrote in one installment, “in which man’s body, mind and soul are in harmony rather than in conflict.” Of Americans’ fright of anything “unsuitable for children,” he said, “Instead of raising children in an adult world, with adult tastes, interests and opinions prevailing, we prefer to live much of our lives in a make-believe children’s world.”

Many, of course, questioned whether Playboy’s outlook could be described as adult. Harvey G. Cox Jr., the Harvard theologian, called it “basically antisexual.” In 1961, in the journal Christianity and Crisis, Dr. Cox wrote: “Playboy and its less successful imitators are not ‘sex magazines’ at all. They dilute and dissipate authentic sexuality by reducing it to an accessory, by keeping it at a safe distance.”

In a 1955 television interview, a frowning Mike Wallace asked Mr. Hefner: “Isn’t that really what you’re selling? A high-class dirty book?”

Such scolding sounded quaint by the time crasser competitors like Penthouse and Hustler appeared in the 1960s and ’70s. Playboy began showing pubic hair on its models, while the others doubled the dare with features on kinkier sexual tastes and close-up photos that bordered on the gynecological. Mr. Hefner would decide, after furious debate among the staff, not to compete further.

Playboy Enterprises still prospered, and in 1971 went public to finance resorts in Jamaica; Lake Geneva, Wis.; and Great Gorge, N.J.; and gambling casinos in London and the Bahamas.

The heady mood broke in 1974, when Mr. Hefner’s longtime personal assistant, Bobbie Arnstein, committed suicide. Ms. Arnstein had just been convicted of conspiracy to distribute cocaine, and Mr. Hefner said bitterly that investigators had hounded her to set him up.

He left Chicago for his second home in Los Angeles, an enormous mock-Tudor house in Holmby Hills with a grotto and a zoo (Mr. Hefner loved animals), where he could orchestrate the company’s move into films.

The 1980s brought a huge retrenchment for Playboy. The company lost its London casinos in 1981 for gambling violations and was denied a gambling license in Atlantic City, partly because of reports that Mr. Hefner had been involved in bribing New York officials for a club license 20 years earlier.

The company shed its resorts and record division and sold Oui magazine, a more explicit but less successful version of Playboy, while the flagship’s circulation plunged. The Playboy Building in Chicago, its rabbit-head beacon illuminating Michigan Avenue, was also sold, as was the corporate jet with built-in discothèque. Bunnies were going the way of go-go dancers, and the Playboy Clubs closed.

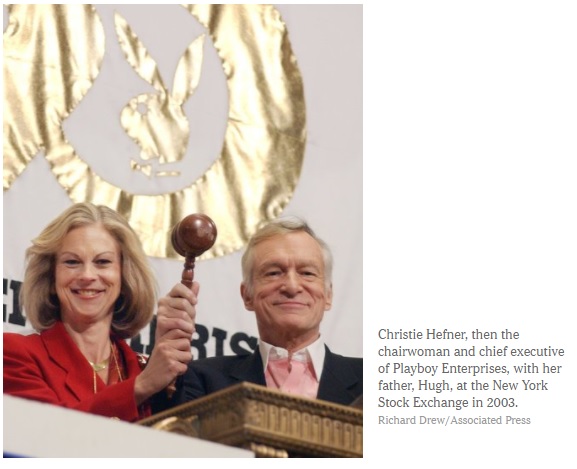

Mr. Hefner relied more and more on his daughter, Christie, named company president in 1982 and then chief executive, a position she held until 2009. Mr. Hefner suffered a stroke in 1985, but he recovered and remained editor in chief of Playboy, choosing the centerfold models, writing captions and tending to detail with an intensity that led his staff to call him “the world’s wealthiest copy editor.”

In 1989 Mr. Hefner married again, saying he had rethought Woody Allen’s line that “marriage is the death of hope.” His second wife was Kimberley Conrad, the 1989 Playmate of the Year, 38 years his junior. They had two sons: Marston Glenn, born in 1990, and Cooper Bradford, born in 1991.

The couple divorced in 2010, and Mr. Hefner plowed into his work, including the editing of “The Century of Sex,” a Playboy book. When a New York Times interviewer later prodded him about the rewards of marriage, he replied, “Unfortunately, they come from other women.” Meanwhile, to widespread snickering, he became a cheerleader for Viagra, telling a British journalist, “It is as close as anyone can imagine to the fountain of youth.”

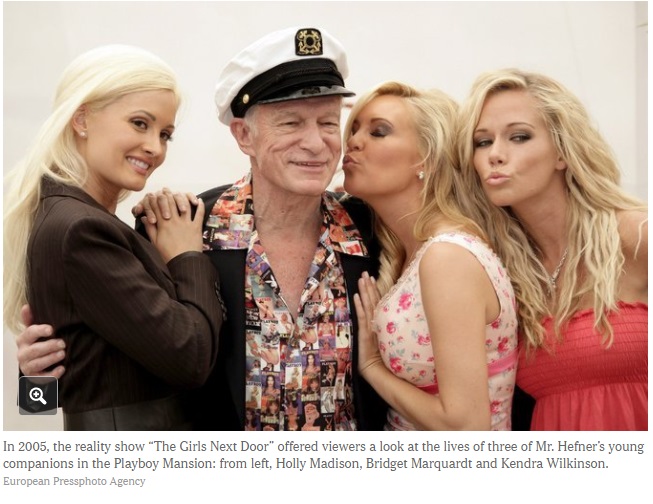

The re-emerged Hef reveled in the new century. In 2005 he began appearing on television on the E! channel reality show “The Girls Next Door,” although his onscreen role consisted mostly of peering in while his three young, blond girlfriends planned adventures at the mansion. When the three original “Girls Next Door” went their separate ways after five seasons, he replaced them with three others, also young and blond — and shortly afterward asked one of them, Crystal Harris, to marry him.

Five days before the 85-year old Mr. Hefner was to marry the 25-year-old Ms. Harris in June 2011 — the wedding was to have been filmed by the Lifetime cable channel as a reality special — the bride called it off. Mr. Hefner, by this time a man of the 21st-century media, announced on Twitter, “Crystal has had a change of heart.”

But Ms. Harris had another change of heart, and the two married on New Year’s Eve 2012. On their first anniversary, Mr. Hefner tweeted to his 1.4 million followers, “It’s good to be in love.”

In addition to his wife, Mr. Hefner’s survivors include his daughter, Christie; and his sons, David, Marston and Cooper.

Another of the “Girls Next Door,” Holly Madison, offered a much more depressing version of life in the mansion in a 2015 tell-all book. In the years when Mr. Hefner was calling her his “No. 1 girlfriend,” she wrote in “Down the Rabbit Hole,” she endured a dysfunctional household of petty rules, allowances, quarrels and backstabbing, all directed by an emotionally manipulative old man.

Through those years, however, the Playboy brand marched forward. In 2011 Mr. Hefner took Playboy Enterprises private again. Mr. Flanders, after taking over as chief executive in 2009, focused on the licensing business, shrinking the company and raising its profits. The website, cleansed of any whiff of pornography, enjoyed huge growth, while Mr. Hefner, who retained his title and about 30 percent of the company’s stock, cheerfully tweeted news and pictures of the many festivities at the mansion, along with hundreds of photographs from his past, in the glory decades of the ’60s and ’70s.

Mr. Hefner will be buried in Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles, where he bought the mausoleum drawer next to Marilyn Monroe.

New York Times Matthew Haag and Zach Johnk contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on September 28, 2017, on Page B16 of the New York edition with the headline:

.gif)