Seminole Gaming and CEO Jim Allen are on the move in the U.S. and in no small way by David McKee

Florida’s Seminole Tribe is feeling bullish about the future of its gambling operations, including its two Hard Rock-branded casinos. On Dec.20, it bestowed a five-year contract extension upon CEO James F. Allen, and granted shorter extensions to Hard Rock International CEO Hamish Dodds (three years) and Seminole Gaming CFO Brad Buchanan. In an additional spate of executive hiring, it snapped up former Borgata president Larry Mullin, installing him as Seminole Gaming’s chief operating officer. Projects either going up or in development under the Hard Rock imprimatur literally span the globe from Hungary to the city of Haikou, in China.

Due to a schism between Hard Rock co-founders Isaac Tigrett and Peter Morton, the Seminoles do not have worldwide control of the brand, which they acquired from the Rank Organisation in 2007. The former Morton territories, mainly west of the Mississippi River, are now owned by Credit Suisse. However, due to Seminole Gaming’s corporate structure, the terms ‘Seminole’ and ‘Hard Rock’ are largely interchangeable. Seminole Gaming is directly responsible for seven Florida casinos. A Virgin Islands- based entity, Hard Rock International, exploits the brand outside the state lines of Florida. The latter has a discrete board of directors, chaired by Allen, who says, “we have the ability to do anywhere in the world the Hard Rock Hotel, the Hard Rock Cafe, Hard Rock Live, Hard Rock Retail or any other affiliation with the brand.”

This has led to some ongoing unpleasantness and litigation between the Seminoles, who own a Hard Rock Cafe at the Harmon-Paradise intersection in Las Vegas, and Credit Suisse, whose Hard Rock Hotel & Casino sits right behind it. While the HRH was under the management and partial ownership of Morgans Hotel Group (subsequently ousted in favor of Warner Gaming), the Seminoles sued to have the Hard Rock moniker taken off the HRH. The causus belli was the hotel’s notorious weekend pool party, Rehab, which the lawsuit described as “a destination that revels in drunken debauchery, acts of vandalism, sexual harassment, violence, criminality and a host of other behavior” that had damaged the brand equity of Hard Rock. (Since the litigation is still pending, Allen cannot comment upon it.)

Four states, four projects

In the American casino industry alone, Seminole Gaming has three, perhaps four irons in the fire. Despite calling off a proposal for a Holyoke casino, Hard Rock continues to scour western Massachusetts for a resort site. “We do believe that we will be submitting a gaming license application and project by the January 15 deadline,” Allen insisted, when interviewed by Casino Life.

He wasn’t kidding. On Jan. 11, Hard Rock International announced that it had a site and had submitted its $400,000 fee to be considered for the highly coveted western-Massachusetts license.

It would partner with Eastern States Exposition to erect Hard Rock Hotel & Casino New England on 38 acres of ESE’s West Springfield campus, best known as the site of the “Big E” agricultural fair. Springfield newspaper The Republican pegs the project cost at $700 million-$800 million. Among the amenities that money will buy: as many as 125 table games, 3,000 slots and 500 hotel rooms, with 150,000 square feet set aside for restaurants. It’s also well above the $500 million minimum investment required by the Bay State.

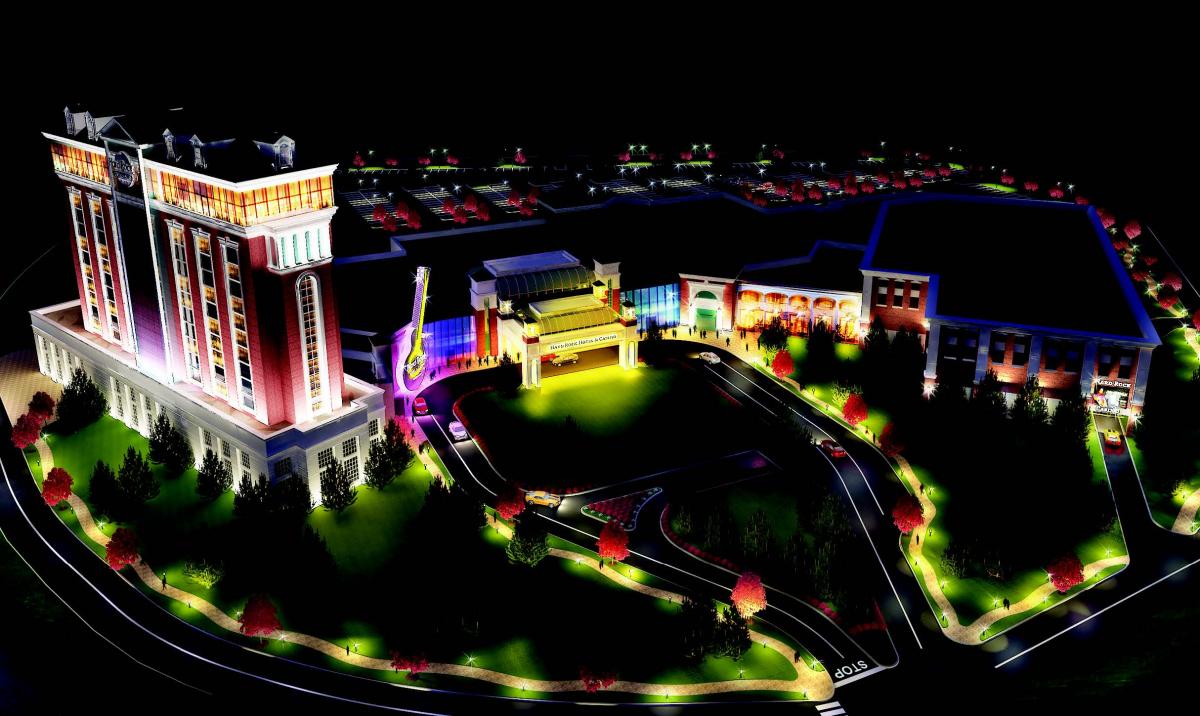

In Northfield, Ohio, Hard Rock is bringing its brand to a new ‘racino’ that will augment the Northfield Park harness-racing track. The $275 million joint venture will place 2,500 VLTs in a stand-alone facility next to Northfield Park’s grandstand. Not only will the iconic oversized-guitar logo of Hard Rock front the building but, when a proposed hotel wing is built, the outline of the structure – if seen from the air – will closely resemble the body and fretboard of an electric guitar.

Track owner Brock Milstein, whose father co-founded the course, “will still focus on the horseracing side of it and we’ll focus on and are responsible for the gaming and entertainment portions,” says Allen.

Although VLTs, upon which players compete against each other, not the house, are often regarded as poor stepchildren to slot machines, Allen insists they are fully competitive. “Visually, they’re identical. The customer would not know the difference. Basically it’s in the technology, taking all the revenues and earnings back to central determination point, so that the state can properly allocate their revenue share and tax percentages,” he explains. “But, from an entertainment standpoint, speed, graphics, etcetera, they’re identical.”

Most prestigiously of all, Hard Rock was tapped to manage The Provence, the downtown casino that Philadelphia-based developer Bart Blatstein has proposed for the city’s old Inquirer building, on North Broad Street, in the heart of the City of Brotherly Love. The former newspaper offices will be converted into a hotel, with the goal of preserving the building’s overall character. Adjoining low-rise structures, on the west side of the site, will hold the casino floor, guest parking and “a great percentage of the amenities,”according to Allen. “It has the right access, and we believe that the legendary, historically protected Philadelphia Inquirer building is one of the iconic buildings in the last 100 years of the Philadelphia skyline.”

Allen also likes the demographics of the area. Not only is the Convention Center close at hand, he depicts the immediate neighborhood as one dominated by apartments and condominiums –implying the kind of high discretionary income that is a casino’s lifeblood. Perhaps the biggest asset is Blatstein’s longstanding relationship to the city itself. Allen characterizes the developer as someone who has gone into and reenergized parts of Philadelphia that the gaming executive diplomatically describes as “maybe not in a thriving economic tradition.” Philadelphia magazine characterizes Blatstein as “the most creative developer this city has seen in a generation,” albeit a very complex and sometimes difficult individual. The Provence is but one component in a four-block Blatstein master plan that, if realized, will include two high-rises and an entertainment complex. In terms of ambition, he’s the equal of Vegas high rollers like Steve Wynn.

Beached on the Boardwalk?

Since the selection process – in which Blatstein is vying against Wynn Resorts, Penn National Gaming and several other aspirants – is expected to take a year, that gives Seminole Gaming plenty of time to contemplate the Hard Rock-branded ‘boutique casino’ that was announced for Atlantic City, then shelved. The $300 million, 200-room project would have sat at the southern edge of the seaside casino district. However, the Seminoles were planning it at a time when older, much larger casinos were changing hands for one-tenth of that price. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Suzette Parmley, an investor revealed that obtaining “financing for a new casino development in Atlantic City right now would be nearly impossible.” Severe underperformance by $2.4 billion Revel was scaring away financiers.

“To be fair to Revel,” says Allen, “that project was conceived back in late 2004-2005 and was designed when the market and the general economics of the United States were much different,” Allen says. Casino revenues on the Boardwalk were still rising, hitting their peak in 2006.” Hard Rock is taking a wait-and- see attitude toward the market. While state officials have been very supportive, “we’ve elected at this particular point not to submit our gaming-license application but we’ve no further comment on Atlantic City.” Allen elaborates that “while certainly the Atlantic City market has been challenged the last 40 months, down from a $5.6 billion in gaming revenues to this year -- we’re probably going to come in around $3.1 billion -- it still is a major gaming market.”

Although Hard Rock has made noises about expanding its casino foothold in Latin America, Allen plays his cards pretty close to the vest. He mentions no specific nation but does point to his company’s track record managing Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Punta Cana, in the Dominican Republic: “It certainly demonstrates the brand is received very favorably and positively in that part of the world.”

Vegas vs. Hard Rock

Closer to home, in Florida, the Seminoles have fended off one challenge to their exclusive right to offer full, Vegas-style gambling on their reservations. Both Las Vegas Sands and Genting Berhad lobbied hard in 2012 for the Florida Legislature to breach the state’s compact with the Seminoles. Ironically, Genting is a business partner with Hard Rock in Singapore’s Resorts World Sentosa complex, where HRI owns a hotel. That isn’t expected to stop Genting, which has purchased expensive, oceanfront real estate in Miami, from coming back from a second try.

What gives legislators pause is whether to abandon a bird in the hand -- $250 million in existing, annual tax revenue from the Seminoles – for two in the bush, in the form of blue-sky financial projections from Sands, Genting, Wynn and others. All of the latter projects would face a much higher profitability threshold than the Seminole ones, their CEOs having promised to throw billions of dollars into each. “We honor and abide by the compact,” Allen remarks, adding ominously that it addresses “the possible complete elimination of all revenue share for all Seminole Tribes in the State of Florida.”

When Casino Life spoke with Allen, he was fresh off the opening of Jubao Palace within Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Tampa. It’s a 17-table, multilingual, casino-within-a-casino, marketed to local Chinese- and Vietnamese-American players. Pai Gow and mini-baccarat dominate the gambling on offer. New amenities “respecting the traditions of the Asian community,” were Seminole Gaming’s goal.

“Whether it be jazz, blues, Asian, Latin – there’s so many different walks of life,” Allen concludes with manifest pride. “We have the ability to create markets within markets with the amazing diversity that we have. Hard Rock doesn’t represent Rock ‘n Roll. It represents music on a worldwide basis. It represents [the] tremendous philanthropic efforts of all of our employees and the principles that Peter and Isaac formed in 1971: ‘Love All, Serve All. Save the Planet.’”